The evolution of teaching and learning

Whether implicit or explicit, we all have a theory of teaching and learning. This gets expressed and enacted in how we engage with our students, the tools we use (or don’t use), and even where we stand in the classroom (F2F or virtually). Traditional theoretical frameworks can be broadly grouped into four domains: instructivism, critical theory, constructivist approaches and andragogy (or adult learning). But the rise of many-to-many, decentred and non-linear networking and communication channels have given rise to corresponding advances in frameworks for teaching and learning in the global classroom.

The 1.0 Classroom

Instructivism as a standard approach to teaching emerged from positivist and post-positivist paradigms. Characterized by the traditional “chalk and talk” style, instructivist pedagogy is premised on a transmission model of learning. Learning outcomes and curricula are pre-determined and delivered in a primarily didactic fashion. The same information is provided to all learners regardless of their pre-existing knowledge and skills.

Teaching 2.0

Constructivism marked a shift from teacher-centred to student-centred learning, deemphasizing informing (memorizing facts) in favour of transforming: locating, critiquing and synthesizing knowledge in a culture of collaboration and sharing. Curriculum development is based on student query, which acknowledges that students learn more by asking questions than by answering them. In this model, students critically engage with course material by posing questions that further group reflection and debate. Adult learning (andragogy) and critical approaches extend and complement contructivist learning models.

Constructivism marked a shift from teacher-centred to student-centred learning, deemphasizing informing (memorizing facts) in favour of transforming: locating, critiquing and synthesizing knowledge in a culture of collaboration and sharing. Curriculum development is based on student query, which acknowledges that students learn more by asking questions than by answering them. In this model, students critically engage with course material by posing questions that further group reflection and debate. Adult learning (andragogy) and critical approaches extend and complement contructivist learning models.

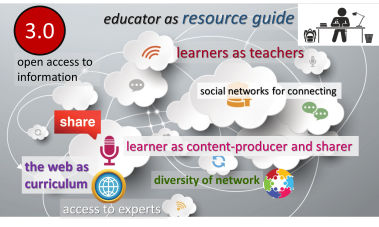

Education 3.0

Over the last decade, two models have emerged to challege our existing paradigms: heutagogy (Blaschke, 2012, Hase and Kenyon, 2000) and paragogy (Corneli and Danoff, 2011). These extend constructivist, critical and adult learning theories offering models of learning that are (1) self-determined, (2) peer-led,

(3) decentred and (4) non-linear. These characteristics map onto social media applications and the democratization of knowledge and information. Heutagogical and paragogical approaches also extend traditional andragogical and adult learning frameworks by emphasizing meta learning, or learning how to learn.

(3) decentred and (4) non-linear. These characteristics map onto social media applications and the democratization of knowledge and information. Heutagogical and paragogical approaches also extend traditional andragogical and adult learning frameworks by emphasizing meta learning, or learning how to learn.

Andragogy, Heutagogy and Social Media

| Andragogy (Self-directed) | Heutagogy (Self-determined) | Parallels with Social Media |

| Competency development | Capability development | Knowledge curators |

| Linear design of curricula | Non-linearity in curricula | Hyper-learners |

| Instructor/learner directed | Learner directed | Autonomous digital communities |

| Content focus (what is learned) | Process focus (meta learning, learning how to learn) | Online collaboration, sharing, crowd-sourcing |

This shift is radical in challenging the implicit notion that we (educators) know best what students need to learn. As Morris (2013) puts it, the issue of how to modify or reinvent teaching in higher education “can create anxiety, uncertainty, and even resentment toward a shift in the culture of learning that we’ve had little control over, that’s come at us from outside our own domain; for others, this new landscape appears inviting, exciting, and full of possibility”.

Radically self-determined and networked learning approaches (like heutagogy and paragogy) affirm individuals as the experts in their lives and learning trajectories. Nothing less than what has always been.

Note: Images depicting Education 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 were adapted from a blog post by Jackie Gerstein: Experiences in Self-Determined Learning: Moving from Education 1.0 Through Education 2.0 Towards Education 3.0

This post was adapted from a previous article.